As flames leapt out of the Capitol Building and the White House, the night sky glowed red as the American people fled Washington. The British were attacking American seaports and the mainland relentlessly, steadily moving toward Baltimore. Emboldened by victory, British Admiral Cochrane informed James Monroe, America’s Secretary of State, that the British Navy had set their eyes on the demolition of Fort McHenry, a pentagonal bastion fort protecting the Baltimore harbor.

A young lawyer named Francis Scott Key had been sent to negotiate the release of prisoners being held on British ships in the Baltimore Harbor. After the successful negotiation of the release, Key was informed by Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane that the negotiations would be fruitless, as the British would launch an attack on Fort McHenry at dawn. Because Key had seen the British preparing to attack, Cochrane did not allow him to return to land.

A young lawyer named Francis Scott Key had been sent to negotiate the release of prisoners being held on British ships in the Baltimore Harbor. After the successful negotiation of the release, Key was informed by Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane that the negotiations would be fruitless, as the British would launch an attack on Fort McHenry at dawn. Because Key had seen the British preparing to attack, Cochrane did not allow him to return to land.

On Tuesday, September 13, 1814, the earth-shattering sound of heavy guns broke the morning calm. British ships, as far as the eye could see, filled the harbor and mercilessly released their deadly mortars. By the following morning, the British had launched over 1,500 mortars, some as heavy as 250 pounds, into Fort McHenry.

Through the night, Key kept a watch over the Fort. As the bombs lit up the night, Key strained to see if the American Flag was still flying. Why? Why was Key so intensely watching the flag? British officers had informed American troops that the whole battle could be avoided if they simply would lower their flag. So, as long as the flag remained raised, the British would continue to attack. For 25 hours, the British bombarded Fort McHenry. For 25 hours, American troops inside the fort made sure that the flag was still there. After 25 hours, the British realized they would not take the fort by sea, and ceased fire.

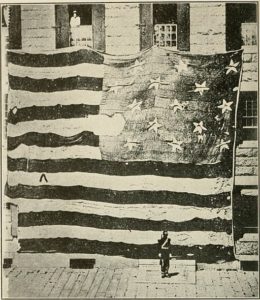

Realizing the British were discontinuing their fire, Key, several miles out, looked over the waters. What would he tell the American prisoners now aboard his ship? Would he see the flag with her bold stripes and bright stars? Would he see the sign of surrender? Did that star-spangled banner yet wave? As the dawn turned to daylight, though its pole was askew and its stars and stripes marred, Key saw that, indeed, our American flag was still there.

You can see the Great Garrison Flag that survived the attack on Fort McHenry at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

The young lawyer penned the first stanza of “The Defense of Fort McHenry” as the smoke began to clear. Shortly after he reached his hotel room, Francis Scott Key wrote the next three stanzas. Later that evening, Key’s brother-in-law, Judge Joseph Nicholsen, read the poem and promptly had it printed. Judge Nicholsen suggested that the poem be sung to “Anacreon in Heaven,” a tune widely sung in taverns throughout America at that time. By September 20, the Baltimore Patriot printed the song in its newspaper. By 1815, the song was known as “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

The song quickly became a favorite. In fact, P.T. Barnum sporadically held “national anthem contests” and no other song had stronger support than The Star-Spangled Banner. By 1889, it had become America’s unofficial anthem. The United States Navy played the song at flag raisings and around 1903, the United States Army had adopted the song. President Woodrow Wilson proclaimed it to be the national anthem and on March 3, 1931, Congress made it official.

In 1931, 36 U.S. Code 301 was written. This law discusses the protocol for our National Anthem. Section (C) states: “all other persons present should face the flag and stand at attention with their right hand over the heart, and men not in uniform, if applicable, should remove their headdress with their right hand and hold it at the left shoulder, the hand being over the heart”. However, by 1943, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled this law as unconstitutional. Today, of course, there is no legal consequence for those who choose not to stand for our National Anthem.

In 1931, 36 U.S. Code 301 was written. This law discusses the protocol for our National Anthem. Section (C) states: “all other persons present should face the flag and stand at attention with their right hand over the heart, and men not in uniform, if applicable, should remove their headdress with their right hand and hold it at the left shoulder, the hand being over the heart”. However, by 1943, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled this law as unconstitutional. Today, of course, there is no legal consequence for those who choose not to stand for our National Anthem.

To many Americans, the flag and our national anthem are not just meaningless symbols. Our national anthem and our flag often represent the things we hold dear: our country, the freedom enjoyed by all Americans, and the troops who fought for it. Many Americans proudly stand with tears in their eyes and gratitude in their hearts when our national anthem is performed. Often, veterans take part in the performing of our national anthem and the simultaneous display of our flag. Such displays are meant to inspire gratitude and patriotism!

Singing the national anthem is not just a tradition, it is a reminder that the freedom we all enjoy today wasn’t always so. It was fought for and won time and again—and remembers our soldiers from today back to that night when Mr. Key strained to see that our flag was still there and on to those who first earned the independence of America.

Singing the national anthem is not just a tradition, it is a reminder that the freedom we all enjoy today wasn’t always so. It was fought for and won time and again—and remembers our soldiers from today back to that night when Mr. Key strained to see that our flag was still there and on to those who first earned the independence of America.

Dayspring Christian Academy uses primary sources to educate students as they seek the truth in America’s history. Fifth-grade Dayspring students visit Fort McHenry as a part of their study of the founding of our nation, including the War of 1812 and the origins of our national anthem. Our method of education, The Principle Approach, is the kind of education that prevailed during America’s first two hundred years.

If you would like to learn more about Dayspring Christian Academy and the Principle Approach, please call Karol Hasting at 717-285-2000 or register for a private tour using the button below.

Cover photo credit: National Park Service (www.nps.gov), Public Domain.