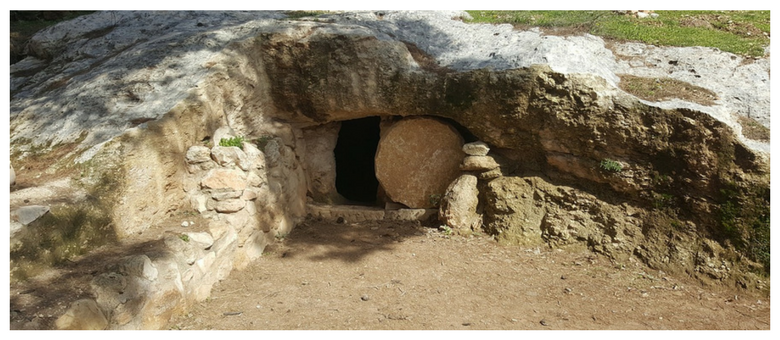

Easter is one of the key Christian observances today, yet it is not mentioned in the Bible! Should we celebrate Easter, and if so, how? I believe that there are four key historic voices of counsel to give us direction concerning Easter celebration.

Voice 1, The Old Testament Feasts

God gave the Israelites a yearly calendar of feast events (Ex. 23, Lev. 23, Deut. 16) that pointed to Christ’s Easter work—that is, His death, burial, and resurrection. The Passover represents His sacrificial death that we might live; it is followed by the Feast of Unleavened Bread, representing our sinless state and our haste to flee the things of the world, once we have received His sacrifice.

A sheaf of firstfruits was to be offered at the beginning of harvest, but 50 days later the Feast of Weeks, or Pentecost, involved an offering of firstfruits. In both of these offerings, Christ is figured as (literally!) the first to come forth from the ground, to be followed by other fruit (His Church), and as the re-appearing first, best fruit when His Church assembled for the coming of His Spirit (Acts 1,2) and for the shaking of the world.

The Feast of Trumpets announces the coming Day of Atonement, similar to the hosanna-filled Triumphal Entry before His atoning work, but also prefiguring the physical raising of the righteous dead at a trumpet blast yet to come (I Cor. 15.52).

The Feast of Tabernacles commemorates Israel’s tenting over the forty years of wilderness wanderings, and reminds the redeemed that we have no permanent dwelling in this world, but also that we do have an abode with the God Who Tabernacled with us in that wilderness, and Who in the Person of the Son, told us just before His sacrifice of the mansions He was going to prepare.

The Feast of Tabernacles commemorates Israel’s tenting over the forty years of wilderness wanderings, and reminds the redeemed that we have no permanent dwelling in this world, but also that we do have an abode with the God Who Tabernacled with us in that wilderness, and Who in the Person of the Son, told us just before His sacrifice of the mansions He was going to prepare.

Matthew Henry comments concerning the feasts that “most [i.e., all but one] were appointed for joy and rejoicing”.

We are not bound to the Old Testament feast calendar (Rom. 14), but Easter is a natural celebration in response to the One Who fulfilled and is fulfilling the principles of those feasts.

Voice 2, The New Testament Day of the Lord

John was “in the Spirit on the Lord’s Day” when, exiled on Patmos and nearing the end of his life, he saw the risen Lord, “the first and the last,…that liveth, and was dead; and, behold [is] alive for evermore” (King James Version, Rev. 1). “On the Lord’s Day” (ἐν τῇ κυριακῇ ἡμέρᾳ, or en tē kuriakē hemera) is thought by some to refer to Easter, but the general consensus among scholars is that it references Sunday. This day became immediately settled in Christian culture as the high day of the week, the weekly celebration of Christ’s resurrection, the day of observing the Lord’s Supper (Acts 20.7; I Cor. 11.20, again using a form of kuriakos, Lord’s, the only New Testament use besides Rev. 1.10), the day of setting aside offerings (I Cor. 16.2).

This Christian calendar phenomenon was counter-cultural. Sunday was a work day. The Christians carved their church meetings and activities into that day as being the specific weekday on which Christ rose. It was like a weekly Easter.

Voice 3, The Fathers’ One Easter

The annual observance of Christ’s resurrection was early established. Irenaeus, in the second century, is credited with bringing peace to the Church over issues of Easter celebration. Cyprian, in his Epistle 23 (written A.D. 250), affirms one Saturus, whom “we had made next to the clergy,” as a reader in the church on Easter Day. Elsewhere he mentions Easter as a great reckoning point in the calendar—other events being often described as falling before or after Easter. Emperor Constantine, at the Council of Nicea (325 AD), gave direction for the scheduling of Easter, because (he wrote), “it was universally thought that it would be convenient that all should keep the feast on one day; for what could be more beautiful and more desirable, than to see this festival, through which we receive the hope of immortality, celebrated by all with one accord, and in the same manner?”

Voice 4, The Pilgrims’ Piety

The observance of Easter over the centuries following the early Fathers became marked by what some deemed as an increasingly worldly celebration spirit, expressed in feasting and show. Reformation figures called Christians to simplicity, humility, and gravity in their devotions to God, so that such as the Pilgrims abjured the celebration of the great feast days, including Easter and Christmas. Of course, they strictly rested and worshiped on the weekly “Easter,” the Sabbath. Though we may not agree with the idea of passing the Easter point in the yearly calendar without a special, greater focus on Christ’s historic death, burial and resurrection, we do indeed need to heed the Pilgrims’ call to piety in our day and in our nation where insincerity, silliness and obliviousness can—in our very churches—mar our historic devotions.

The observance of Easter over the centuries following the early Fathers became marked by what some deemed as an increasingly worldly celebration spirit, expressed in feasting and show. Reformation figures called Christians to simplicity, humility, and gravity in their devotions to God, so that such as the Pilgrims abjured the celebration of the great feast days, including Easter and Christmas. Of course, they strictly rested and worshiped on the weekly “Easter,” the Sabbath. Though we may not agree with the idea of passing the Easter point in the yearly calendar without a special, greater focus on Christ’s historic death, burial and resurrection, we do indeed need to heed the Pilgrims’ call to piety in our day and in our nation where insincerity, silliness and obliviousness can—in our very churches—mar our historic devotions.

The Voices All

Easter! Let us hear all the voices. The Old Testament tells us to celebrate joyfully our Lord’s great work. The New Testament tells us to order our lives around the resurrection of the Christ. The Church Fathers tell us to observe Easter in unity. The Pilgrims move us to piety. These great believers from these different ages have done their part of teaching us; may we do our part to teach, and to celebrate in intelligent, unified, pious joy the resurrection of the Lord of the Universe, Who is the hope of life eternal, and the bringer now of life abundant.

If you would like more information about Dayspring Christian Academy or The Principle Approach, please contact Karol Hasting at 717-285-2000.